Some images in this post are not safe for work.

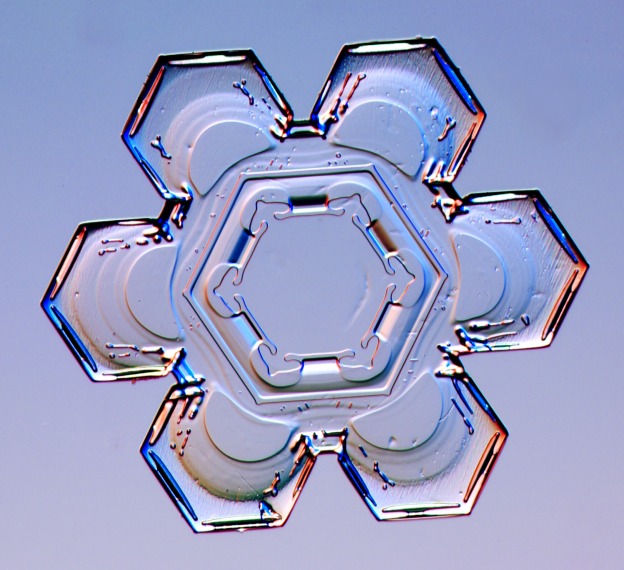

By the time you read this, the ink will be drying on my first ever tattoo, a decorative hexagonal design based on the crystalline shapes that form when water freezes. This snowflake motif was inspired by a weekend I spent in Warsaw with a dear friend of long standing (let's call her Celine) five years ago this month. I've chosen to put it on the inside of my right upper arm, where I can display or conceal it as the fancy takes me.

Attitudes to body art have changed significantly in the last ten years with more and more people going under the needle. It's no longer considered as vulgar to sport a fine line tattoo on the forearm as it was a decade ago and if not for these changing mores I'd be unlikely to consider wearing such visible ink myself. But perhaps the question is not why permanent skin embellishment is creeping back into favour, but why it should be considered improper in the first place.

|

| Traditional Samoan Pe'a tattoo, via wikipedia |

The practice of injecting ink into the skin to create indelible markings has a long and not always dishonourable history, with known examples dating back at least 6000 years. Traditional techniques used chisels fashioned from shell or bone, gouging the epidermis to insert pigment during long and torturous processes, with full body coverage achieved in months if not years.

The word tattoo is derived from the Samoan word tatau, meaning "correct" or "workmanlike". Before the arrival of Christian missionaries in the 19th century, every Samoan man would wear the traditional Pe'a design as an expression of his personhood. Reports from Cook's expeditions in the Pacific are often credited with a dramatic resurgence of interest in the art of the tattoo, and although this is almost certainly myth-making, the tribal tattoos of the Polynesian people have been among the most influential in the history of body art. They continue to worn with pride throughout the South Seas as a powerful expression of ethnic identity.

_-_103_Betto.jpg) |

| Irezumi, circa 1875, via wikipedia |

At the other end of the spectrum, the ancient Japanese tradition of irezumi has all but been wiped out in its native culture by its associations with criminality. An 80 year prohibition on body art drove it underground and led to its adoption by the feared Yakuza gangsters. By the time the ban was lifted by occupying forces after WWII, the damage had been done. Today, displaying a visible tattoo can lead to life-changing consequences not only in Japan but elsewhere in the Far East. In spite of this, irezumi survives underground, with a tiny number of masters still practicing, and its refined artistic technique has made it one of the most popular styles in Western culture.

Conflicted attitudes in multicultural societies can lead to a confused response among communities in diaspora, as Margaret Cho discovered when she was ostracised by other customers at a Korean sauna in Los Angeles. Clearly, her heavily tattooed body was too much for the older generation and she was asked to cover up. In all fairness, given the cultural context, the tattooed man Cho spotted in the gym area may well have been a gangster, in which case no staff in their right mind would have asked him to hide his ink. Even so, the loud assertion of I'M MARGARET CHO should be enough to cow anyone into submission.

It seems natural that many of our reasons for wearing artwork on our skin would line up alongside all those things we seek to express with our clothes, such as personal identity, status or membership of a group. But there's another aspect to these permanent markings that goes beyond fashion and cuts straight to the heart of the human condition. For many people, tattoos bear the existential significance of the life experiences that define who we are.

Which brings me back to Celine, my old muckerina and partner in crime.

We first met as scared 11 year olds in the first weeks of secondary school. Neither of us enjoyed the place very much and the early years of our acquaintance as teenagers was awkward and often fraught. Nevertheless, we endured that difficult rite of passage together and our friendship matured as we reached adulthood. And although it proved hard for me to keep up with other folk back home we somehow survived my move to Amsterdam.

|

| Warsaw 14-03-2010 |

Our trip to Warsaw was one of a number of excursions we made together to various European destinations between 2010 and 2013. We spent two days wandering around eating, drinking and generally making merry, negotiating several inches of late winter snow to discover the magic of a beautiful and endlessly surprising city.

Celine had been diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer in 2009 and given a five year sentence. She was forty years old. She'd quit her lucrative but stressful job in investment banking, cashed in her life insurance and was spending the time she had left facing her illness with the kind of courage and dignity that I doubt I'll be able to muster when the time comes, and living as well as only she knew how.

|

| 27-08-2014 |

Celine passed away at the end of last summer just over six months ago. She would have turned 46 last week. One of the last things she did before she died was to buy a few tiny keepsakes for her friends to remember her by. She gave me a little snowflake to commemorate that late snowfall, which I wear on a bracelet. In the weeks after her death it was very comforting to have close by.

Needless to say I soon discovered how impractical it was to wear such a fragile thing all the time and I wanted to put it somewhere I could see it and I wouldn't loose it. I designed a snowflake that I could always wear in memoriam, a simple thing made up of six wine goblets in honour of all the glasses we'd raised together, grouped around the empty space she left behind when she departed.

But there's another reason to commemorate the Warsaw trip, which is an incident which occurred before we even arrived there. We were travelling from Amsterdam on the overnight train in a shared double compartment, with me on the top bunk and Celine on the bottom. Sleep is fitful in even the most luxurious of rail carriages, and I spent the night drifting in and out of consciousness to the sound of squeaking wheels and rattling axels.

Somewhere around Berlin I distinctly recall something unspeakable, familiar from a thousand childhood nightmares, emerging from under the berth and climbing all over my legs. I woke up screaming for help. Of course, there was nobody but Celine in the berth below. She hadn't been sleeping deeply and my nightmare woke her up too. After chemotherapy she always had a certain fearlessness about her and she thought it was hilarious that I'd been disturbed by something so juvenile. She teased me about it all weekend.

I can't help but wonder about that hideous creature that crawled out from under the berth on the train, a being so universal that almost everyone has seen it and would recognise it if they saw it again. I'm quite skeptical by nature, but sometimes I can't help but be touched by coincidence. Celine was one of those people who saw ghosts, or at least believed she did. And if so many of us have seen that thing, then what is it?

The artist in me thrills and recoils at such a tangible manifestation of the disease that killed her growing quietly inside, waiting for the moment to finally rise up and steal her future. When I think of it now, it's not with the terror and desperation that woke me up, but with the ice cold grief that comes from the certainty that in the end we are all just meltwater, and a fragile, crystalline determination to live.

But there's another reason to commemorate the Warsaw trip, which is an incident which occurred before we even arrived there. We were travelling from Amsterdam on the overnight train in a shared double compartment, with me on the top bunk and Celine on the bottom. Sleep is fitful in even the most luxurious of rail carriages, and I spent the night drifting in and out of consciousness to the sound of squeaking wheels and rattling axels.

Somewhere around Berlin I distinctly recall something unspeakable, familiar from a thousand childhood nightmares, emerging from under the berth and climbing all over my legs. I woke up screaming for help. Of course, there was nobody but Celine in the berth below. She hadn't been sleeping deeply and my nightmare woke her up too. After chemotherapy she always had a certain fearlessness about her and she thought it was hilarious that I'd been disturbed by something so juvenile. She teased me about it all weekend.

I can't help but wonder about that hideous creature that crawled out from under the berth on the train, a being so universal that almost everyone has seen it and would recognise it if they saw it again. I'm quite skeptical by nature, but sometimes I can't help but be touched by coincidence. Celine was one of those people who saw ghosts, or at least believed she did. And if so many of us have seen that thing, then what is it?

The artist in me thrills and recoils at such a tangible manifestation of the disease that killed her growing quietly inside, waiting for the moment to finally rise up and steal her future. When I think of it now, it's not with the terror and desperation that woke me up, but with the ice cold grief that comes from the certainty that in the end we are all just meltwater, and a fragile, crystalline determination to live.

Thanks are due to Angie at YouLookFab.com for her insightful commentary on attitudes in the Far East and to the magnificent ladies in the forum for their support during this cathartic process. And to Joey De Boer at HaarBarbaar for his fine work with the needle.

No comments:

Post a Comment